Resilient Onesimus: How an African Slave Transformed Medicine

Written on

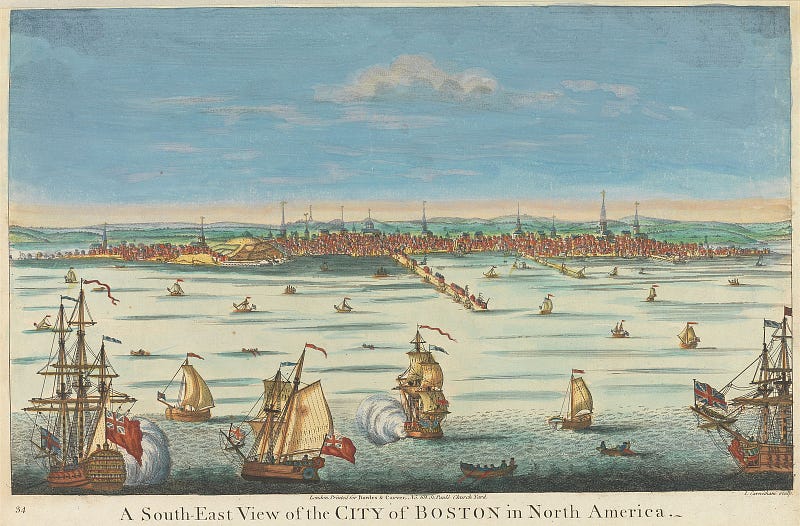

Chapter 1: The Smallpox Crisis in Boston

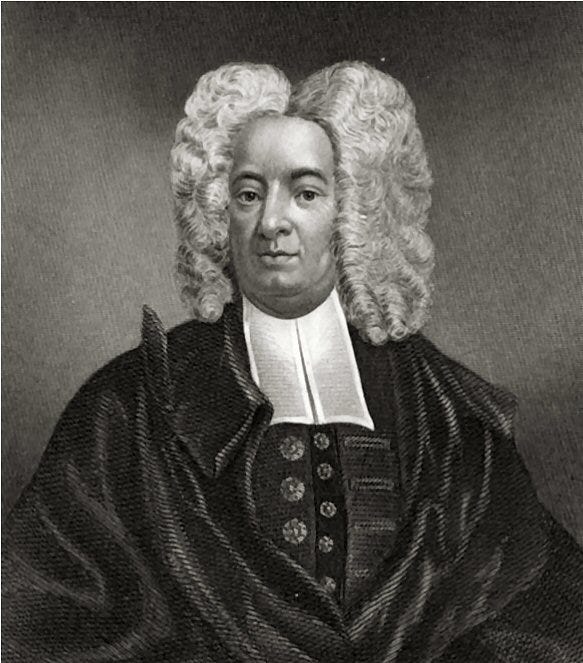

In 1721, Boston found itself in a state of panic as a smallpox outbreak gripped the city. This highly contagious virus, notorious for its 30% mortality rate and disfiguring scars, led to the deaths of numerous residents and prompted many others to flee. With no access to contemporary medical knowledge or vaccines, the city faced the prospect of a catastrophic population loss. However, the situation took a turn for the better, thanks to Onesimus, an African slave, and his master, Reverend Cotton Mather, who drew upon their earlier understanding of medicine.

Chapter 2: Onesimus's Background

Onesimus, whose name translates to "useful" or "beneficial," was brought to America in the early 18th century as a gift for Cotton Mather, a Puritan minister. His keen intellect allowed him to learn reading and writing. In 1716, Onesimus introduced Mather to the practice of inoculation, which involves administering a small amount of the virus to build immunity. He showcased his own scars as evidence of having survived smallpox through this method.

Mather was intrigued by Onesimus's account and later corroborated it with reports detailing similar practices in Turkey and China. He recounted Onesimus’s description of inoculation:

"People take Juice of Small-Pox; and cutty-skin, and putt in a Drop; then by’nd by a little sicky, sicky: then very few little things like Small-Pox; and no body dy of it; and no body have Small-Pox any more."

In 1716, Reverend Mather introduced the concept of inoculation to the medical community, even challenging the work of physician Emanuele Timoni, asserting that he had learned about inoculation long before encountering it in Europe. He noted:

"I do assure you, that many months before I mett with any Intimations of treating the Small-Pox, with the Method of Inoculation, any where in Europe; I had from a Servant of my own, an Account of its being practised in Africa."

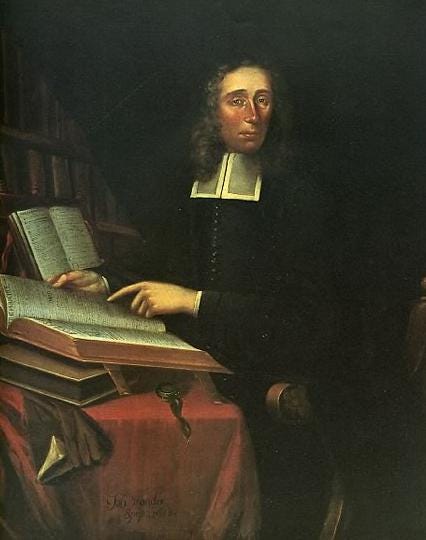

Despite Mather’s efforts, the medical community largely dismissed his findings. When smallpox resurfaced in Boston five years later, Mather seized the opportunity to implement inoculation among the populace. However, this led to a fierce debate between Mather, who saw inoculation as a divine blessing, and William Douglass, a physician who regarded it as mere superstition.

Section 2.1: The Controversy

Douglass was openly skeptical of the intelligence and medical contributions of Africans, deriding Mather's acceptance of Onesimus’s ideas. He remarked sarcastically on the validity of Mather’s story, calling it a "Rare Farce." As a result, Boston's medical community rallied around Douglass due to his established expertise, making it difficult for Mather to gain traction for his views.

Though lacking popular support, Mather did find allies in figures such as Zabdiel Boylston, a doctor-in-training, and fellow clergyman Benjamin Colman. Colman expressed his belief in the significance of Onesimus’s contribution, stating, "I believe I shall be scoff’d at for telling this Simple story, but I think it very pertinent & much to the purpose here."

In 1721, Mather and Boylston initiated a campaign to inoculate Bostonians, starting with Boylston's son and his slaves. Documenting the process in his Historical Account of Small-pox Inoculation in New England, Boylston reported that inoculation was effective for both white and black individuals.

The first video highlights how Onesimus, a slave, brought relief from smallpox to the American colonies, showcasing the vital role he played in medical history.

Mather and Boylston successfully inoculated 242 individuals, with only six fatalities among them, suggesting a mortality rate of 1 in 40 compared to the 1 in 7 chance for those unvaccinated. Ultimately, the outbreak claimed the lives of 844 residents, more than 14% of Boston's population.

Chapter 3: A Legacy for Modern Medicine

Despite the success of Mather’s and Boylston’s inoculation efforts, Douglass’s skepticism shaped the prevailing medical practices of the time, emphasizing empirical observation over what he deemed reckless experimentation. Nevertheless, in 1725, Boylston, with Mather's support, traveled to London to publish his findings, gaining membership in the Royal Society. Their research laid the groundwork for Edward Jenner's development of the world's first vaccine in 1796.

In 1980, the World Health Organization declared smallpox eradicated, marking a monumental achievement in public health.

Did Onesimus ever realize the extent of his contributions? Historical records offer little insight into his later life, but he is known to have partially purchased his freedom and started a family. Although it took centuries to eliminate smallpox, the role of Onesimus—a slave—remains a pivotal chapter in the story of medicine.

The second video commemorates Black History Month by focusing on Onesimus, the African slave whose knowledge played a crucial role in American medical history.