Testing the Fabric of Space-Time with Atomic Clocks

Written on

Chapter 1: Einstein's Relativity and Modern Testing

Recent experiments have once again substantiated the predictions laid out in Einstein's theory of special relativity, crafted over a century ago.

The core principle of Einstein's Special Theory of Relativity posits that the speed of light remains constant for all observers, regardless of their relative motion. A century after this groundbreaking theory was introduced, numerous experimental validations reveal how counterintuitive this notion can be.

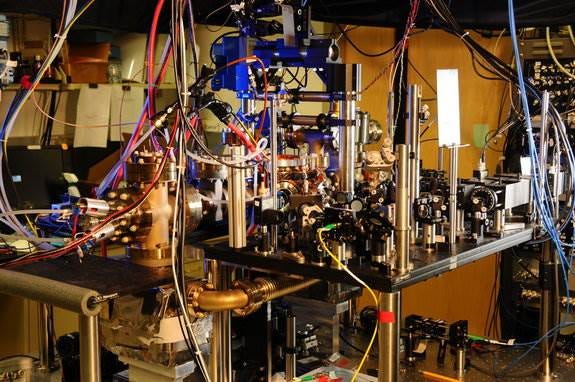

However, theoretical models in quantum gravitation suggest that this uniformity in space-time might not hold for all particles. Researchers from the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB) and the University of Delaware have conducted a pioneering long-term comparison using two optical ytterbium clocks, which capture thousands of ytterbium atoms within laser beam grids.

These advanced clocks, which have a potential error margin of merely one second over ten billion years, enable the detection of incredibly minute variations in the electron movements within ytterbium. The scientists found no discrepancies when the clocks were oriented differently in space. Their findings were published in a recent edition of Nature.

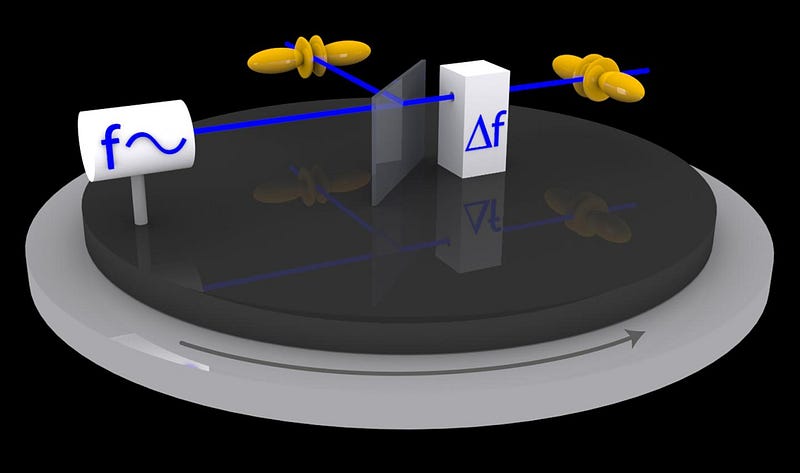

A tunable laser targets a very narrow-band resonance within a Yb+ ion of an atomic clock. The electron wave function of the ion's excited state is highlighted in yellow. Two ions with perpendicular wave functions are analyzed using laser light with variable frequency shifts to detect potential frequency differences. The entire experimental setup rotates with the Earth once daily in relation to the fixed stars (Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB)).

This groundbreaking experiment has enhanced the previous limits for testing space-time symmetry by a factor of 100. Additionally, it affirms the remarkably small systematic measurement uncertainty of optical ytterbium clocks, which is under 4 × 10E-18.

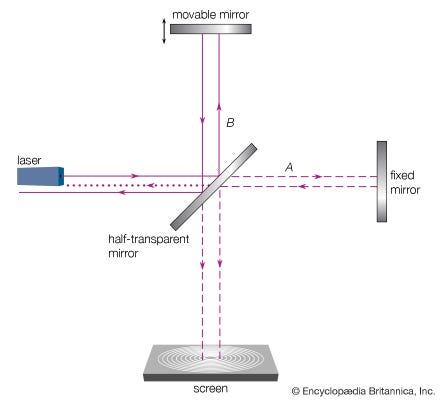

The concept of light's constancy was first unveiled by Michelson and Morley in their renowned 1887 experiment. Utilizing a rotating interferometer, they compared the speed of light along two perpendicular optical axes.

The outcome of this experiment effectively dismissed the existence of the luminiferous aether, the presumed medium for light's propagation, thereby supporting one of the fundamental assertions of Einstein's Special Theory of Relativity—that the speed of light remains constant in all spatial directions.

This discovery prompted scientists to explore whether this spatial symmetry extends to the motion of material particles or if certain directions allow these particles to move faster or slower while maintaining the same energy. For high-energy particles, quantum gravitation theories predict potential violations of symmetry in Lorentz spacetime, named after Hendrik Antoon Lorentz.

To investigate this, an experiment was conducted utilizing two atomic clocks—each frequency governed by the resonance frequency of a single Yb+ ion stored in a trap. In their ground state, the electron distributions of the Yb+ ions are spherically symmetric, while in the excited state, they display a distinctly elongated wave function, predominantly moving along a specific spatial direction.

The wave function's orientation is influenced by a magnetic field within the clock. This field was set approximately at right angles in both clocks. Firmly secured in a laboratory, the clocks rotate with the Earth once every 23.9345 hours relative to the fixed stars.

If the electrons' speed were contingent on spatial orientation, a periodic frequency difference would be expected between the two atomic clocks, corresponding with Earth's rotation.

To identify such an effect, the frequencies of the Yb+ clocks were compared over a span of more than 1000 hours. During this time, no variations were observed between the two clocks, regardless of the measurement periods ranging from a few minutes to 80 hours.

Throughout the total measurement duration, both clocks exhibited a relative frequency deviation of less than 3 × 10E-18. This aligns with the previously estimated combined uncertainty of 4 × 10E-18 for the clock. This achievement marks a significant advance in the precision characterization of optical atomic clocks. After approximately ten billion years, these clocks would potentially differ by just one second, reaffirming the remarkable predictions of Einstein's theories even after a century of scrutiny.

Original research: Christian Sanner, Nils Huntemann, Richard Lange, Christian Tamm, Ekkehard Peik, Marianna S. Safronova, Sergey G. Porsev: Optical clock comparison for Lorentz symmetry testing. Nature (2019)

Chapter 2: Exploring Atomic Clocks and Their Implications

This video discusses NASA's extensive testing of a Deep Space Atomic Clock over two years, exploring its significance and implications for future space missions.

In this video, Jun Ye from Boulder explains the precise engineering of quantum many-body states for atomic clocks and their fundamental importance in physics.